How do things happen in GNOME?

Things happen in GNOME? Could have fooled me, right?

Of course, things happen in GNOME. After all, we have been releasing every

six months, on the dot, for nearly 25 years. Assuming we’re not constantly

re-releasing the same source files, then we have to come to the conclusion

that things change inside each project that makes GNOME, and thus things

happen that involve more than one project.

So let’s roll back a bit.

GNOME’s original sin

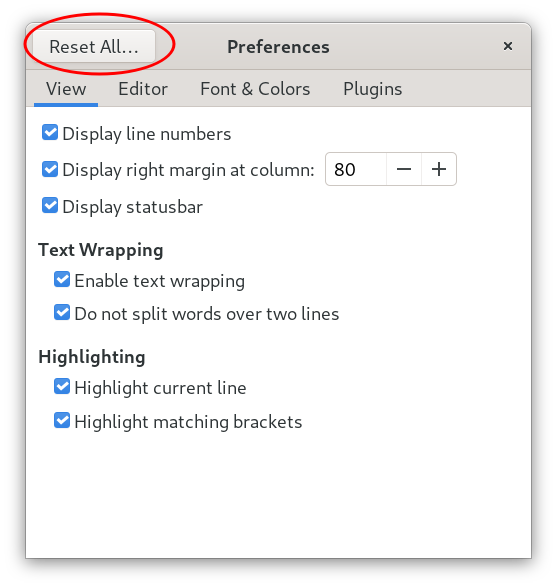

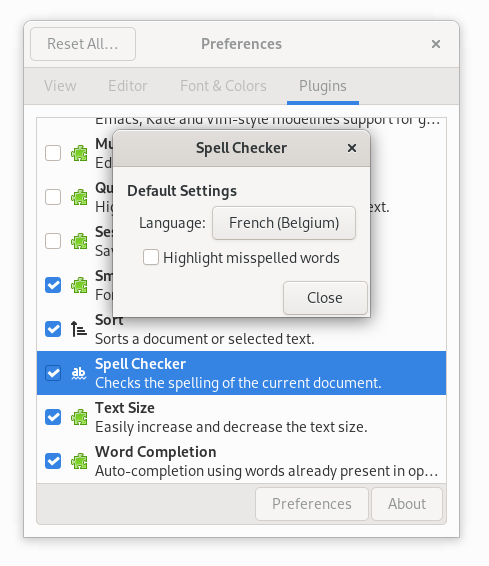

We all know Havoc Pennington’s essay on

preferences; it’s one of GNOME’s

foundational texts, we refer to it pretty much constantly both inside and

outside the contributors community. It has guided our decisions and taste

for over 20 years. As far as foundational text goes, though, it applies to

design philosophy, not to project governance.

When talking about the inception and technical direction of the GNOME project

there are really two foundational texts that describe the goals of GNOME, as

well as the mechanisms that are employed to achieve those goals.

The first one is, of course, Miguel’s announcement of the GNOME project

itself, sent to the GTK, Guile, and (for good measure) the KDE mailing lists:

We will try to reuse the existing code for GNU programs as

much as possible, while adhering to the guidelines of the project.

Putting nice and consistent user interfaces over all-time

favorites will be one of the projects.

— Miguel de Icaza, “The GNOME Desktop project.” announcement email

Once again, everyone related to the GNOME project is (or should be) familiar

with this text.

The second foundational text is not as familiar, outside of the core group

of people that were around at the time. I am referring to Derek Glidden’s

description of the differences between GNOME and KDE, written five years

after the inception of the project. I isolated a small fragment of it:

Development strategies are generally determined by whatever light show happens

to be going on at the moment, when one of the developers will leap up and scream

“I WANT IT TO LOOK JUST LIKE THAT” and then straight-arm his laptop against the

wall in an hallucinogenic frenzy before vomiting copiously, passing out and

falling face-down in the middle of the dance floor.

— Derek Glidden, “GNOME vs KDE”

What both texts have in common is subtle, but explains the origin of the

project. You may not notice it immediately, but once you see it you can’t

unsee it: it’s the over-reliance on personal projects and taste, to be

sublimated into a shared vision. A “bottom up” approach, with “nice and

consistent user interfaces” bolted on top of “all-time favorites”, with zero

indication of how those nice and consistent UIs would work on extant code

bases, all driven by somebody’s with a vision—drug induced or otherwise—that

decides to lead the project towards its implementation.

It’s been nearly 30 years, but GNOME still works that way.

Sure, we’ve had a HIG for 25 years, and the shared development resources

that the project provides tend to mask this, to the point that everyone

outside the project assumes that all people with access to the GNOME commit

bit work on the whole project, as a single unit. If you are here, listening

(or reading) to this, you know it’s not true. In fact, it is so comically

removed from the lived experience of everyone involved in the project that

we generally joke about it.

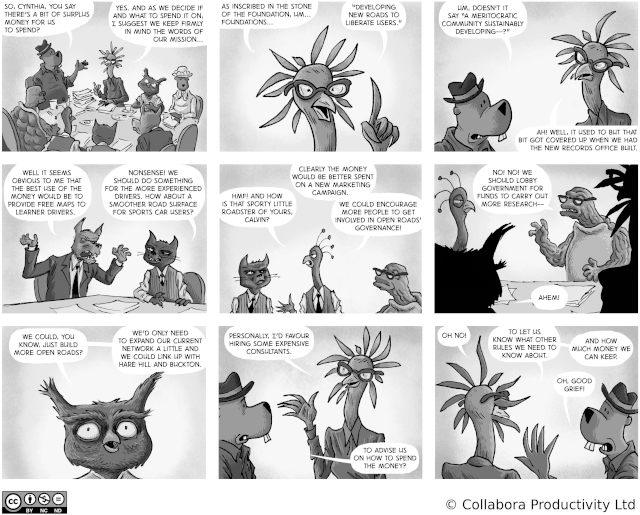

Herding cats and vectors sum

During my first GUADEC, back in 2005, I saw a great slide from Seth Nickell,

one of the original GNOME designers. It showed GNOME contributors

represented as a jumble of vectors going in all directions, cancelling each

component out; and the occasional movement in the project was the result of

somebody pulling/pushing harder in their direction.

Of course, this is not the exclusive province of GNOME: you could take most

complex free and open source software projects and draw a similar diagram. I

contend, though, that when it comes to GNOME this is not emergent behaviour

but it’s baked into the project from its very inception: a loosey-goosey

collection of cats, herded together by whoever shows up with “a vision”,

but, also, a collection of loosely coupled projects. Over the years we tried

to put a rest to the notion that GNOME is a box of LEGO, meant to be

assembled together by distributors and users in the way they most like it;

while our software stack has graduated from the “thrown together at the last

minute” quality of its first decade, our community is still very much

following that very same model; the only way it seems to work is because

we have a few people maintaining a lot of components.

On maintainers

I am a software nerd, and one of the side effects of this terminal condition

is that I like optimisation problems. Optimising software is inherently

boring, though, so I end up trying to optimise processes and people. The

fundamental truth of process optimisation, just like software, is to avoid

unnecessary work—which, in some cases, means optimising away the people involved.

I am afraid I will have to be blunt, here, so I am going to ask for your

forgiveness in advance.

Let’s say you are a maintainer inside a community of maintainers. Dealing

with people is hard, and the lord forbid you talk to other people about what

you’re doing, what they are doing, and what you can do together, so you only

have a few options available.

The first one is: you carve out your niche. You start, or take over, a

project, or an aspect of a project, and you try very hard to make yourself

indispensable, so that everything ends up passing through you, and everyone

has to defer to your taste, opinion, or edict.

Another option: API design is opinionated, and reflects the thoughts of the

person behind it. By designing platform API, you try to replicate your

toughts, taste, and opinions into the minds of the people using it, like the

eggs of parasitic wasp; because if everybody thinks like you, then there

won’t be conflicts, and you won’t have to deal with details, like “how to

make this application work”, or “how to share functionality”; or, you know,

having to develop a theory of mind for relating to other people.

Another option: you try to reimplement the entirety of a platform by

yourself. You start a bunch of projects, which require starting a bunch of

dependencies, which require refactoring a bunch of libraries, which ends up

cascading into half of the stack. Of course, since you’re by yourself, you

end up with a consistent approach to everything. Everything is as it ought

to be: fast, lean, efficient, a reflection of your taste, commitment, and

ethos. You made everyone else redundant, which means people depend on you,

but also nobody is interested in helping you out, because you are now taken

for granted, on the one hand, and nobody is able to get a word edgewise into

what you made on the other.

I purposefully did not name names, even though we can all recognise somebody

in these examples. For instance, I recognise myself. I have been all of

these examples, at one point or another over the past 20 years.

Painting a target on your back

But if this is what it looks like from within a project, what it looks like

from the outside is even worse.

Once you start dragging other people, you raise your visibility; people

start learning your name, because you appear in the issue tracker, on

Matrix/IRC, on Discourse and Planet GNOME. Youtubers and journalists start

asking you questions about the project. Randos on web forums start

associating you to everything GNOME does, or does not; to features, design,

and bugs. You become responsible for every decision, whether you are or not,

and this leads to being the embodiment of all evil the project does. You’ll

get hate mail, you’ll be harrassed, your words will be used against you and

the project for ever and ever.

Burnout and you

Of course, that ends up burning people out; it would be absurd if it didn’t.

Even in the best case possible, you’ll end up burning out just by reaching

empathy fatigue, because everyone has access to you, and everyone has their

own problems and bugs and features and wouldn’t it be great to solve every

problem in the world? This is similar to working for non profits as opposed

to the typical corporate burnout: you get into a feedback loop where you

don’t want to distance yourself from the work you do because the work you do

gives meaning to yourself and to the people that use it; and yet working on

it hurts you. It also empowers bad faith actors to hound you down to the

ends of the earth, until you realise that turning sand into computers was a

terrible mistake, and we should have torched the first personal computer

down on sight.

Governance

We want to have structure, so that people know what to expect and how to

navigate the decision making process inside the project; we also want to

avoid having a sacrificial lamb that takes on all the problems in the world

on their shoulders until we burn them down to a cinder and they have to

leave. We’re 28 years too late to have a benevolent dictator, self-appointed

or otherwise, and we don’t want to have a public consultation every time we

want to deal with a systemic feature. What do we do?

Examples

What do other projects have to teach us about governance? We are not the

only complex free software project in existence, and it would be an appaling

measure of narcissism to believe that we’re special in any way, shape or form.

Python

We should all know what a Python PEP is, but if

you are not familiar with the process I strongly recommend going through it.

It’s well documented, and pretty much the de facto standard for any complex

free and open source project that has achieved escape velocity from a

centralised figure in charge of the whole decision making process. The real

achievement of the Python community is that it adopted this policy long

before their centralised figure called it quits. The interesting thing of

the PEP process is that it is used to codify the governance of the project

itself; the PEP template is a PEP; teams are defined through PEPs; target

platforms are defined through PEPs; deprecations are defined through PEPs;

all project-wide processes are defined through PEPs.

Rust

Rust has a similar process for language, tooling, and standard library

changes, called “RFC”. The RFC process

is more lightweight on the formalities than Python’s PEPs, but it’s still

very well defined. Rust, being a project that came into existence in a

Post-PEP world, adopted the same type of process, and used it to codify

teams, governance, and any and all project-wide processes.

Fedora

Fedora change proposals exist to discuss and document both self-contained

changes (usually fairly uncontroversial, given that they are proposed by the

same owners of module being changed) and system-wide changes. The main

difference between them is that most of the elements of a system-wide change

proposal are required, wheres for self-contained proposals they can be

optional; for instance, a system-wide change must have a contingency plan, a

way to test it, and the impact on documentation and release notes, whereas

as self-contained change does not.

GNOME

Turns out that we once did have “GNOME Enhancement

Proposals” (GEP), mainly modelled on

Python’s PEP from 2002. If this comes as a surprise, that’s because they

lasted for about a year, mainly because it was a reactionary process to try

and funnel some of the large controversies of the 2.0 development cycle into

a productive outlet that didn’t involve flames and people dramatically

quitting the project. GEPs failed once the community fractured, and people

started working in silos, either under their own direction or, more likely,

under their management’s direction. What’s the point of discussing a

project-wide change, when that change was going to be implemented by people

already working together?

The GEP process mutated into the lightweight “module proposal” process,

where people discussed adding and removing dependencies on the desktop

development mailing list—something we also lost over the 2.x cycle, mainly

because the amount of discussions over time tended towards zero. The people

involved with the change knew what those modules brought to the release, and

people unfamiliar with them were either giving out unsolicited advice, or

were simply not reached by the desktop development mailing list. The

discussions turned into external dependencies notifications, which also died

up because apparently asking to compose an email to notify the release team

that a new dependency was needed to build a core module was far too much of

a bother for project maintainers.

The creation and failure of GEP and module proposals is both an indication

of the need for structure inside GNOME, and how this need collides with the

expectation that project maintainers have not just complete control over

every aspect of their domain, but that they can also drag out the process

until all the energy behind it has dissipated. Being in charge for the long

run allows people to just run out the clock on everybody else.

Goals

So, what should be the goal of a proper technical governance model for the

GNOME project?

Diffusing responsibilities

This should be goal zero of any attempt at structuring the technical

governance of GNOME. We have too few people in too many critical positions.

We can call it “efficiency”, we can call it “bus factor”, we can call it

“bottleneck”, but the result is the same: the responsibility for anything is

too concentrated. This is how you get conflict. This is how you get burnout.

This is how you paralise a whole project. By having too few people in

positions of responsibility, we don’t have enough slack in the governance

model; it’s an illusion of efficiency.

Responsibility is not something to hoard: it’s something to distribute.

Empowering the community

The community of contributors should be able to know when and how a decision

is made; it should be able to know what to do once a decision is made. Right

now, the process is opaque because it’s done inside a million different

rooms, and, more importantly, it is not recorded for posterity. Random

GitLab issues should not be the only place where people can be informed that

some decision was taken.

Empowering individuals

Individuals should be able to contribute to a decision without necessarily

becoming responsible for a whole project. It’s daunting, and requires a

measure of hubris that cannot be allowed to exist in a shared space. In a

similar fashion, we should empower people that want to contribute to the

project by reducing the amount of fluff coming from people with zero stakes

in it, and are interested only in giving out an opinion on their perfectly

spherical, frictionless desktop environment.

It is free and open source software, not free and open mic night down at

the pub.

Actual decision making process

We say we work by rough consensus, but if a single person is responsible for

multiple modules inside the project, we’re just deceiving ourselves. I

should not be able to design something on my own, commit it to all projects

I maintain, and then go home, regardless of whether what I designed is good

or necessary.

Proposed GNOME Changes✝

✝ Name subject to change

PGCs

We have better tools than what the GEP used to use and be. We have better

communication venues in 2025; we have better validation; we have better

publishing mechanisms.

We can take a lightweight approach, with a well-defined process, and use it

not for actual design or decision-making, but for discussion and

documentation. If you are trying to design something and you use this

process, you are by definition Doing It Wrong™. You should have a design

ready, and series of steps to achieve it, as part of a proposal. You should

already know the projects involved, and already have an idea of the effort

needed to make something happen.

Once you have a formal proposal, you present it to the various stakeholders,

and iterate over it to improve it, clarify it, and amend it, until you have

something that has a rough consensus among all the parties involved. Once

that’s done, the proposal is now in effect, and people can refer to it

during the implementation, and in the future. This way, we don’t have to ask

people to remember a decision made six months, two years, ten years ago:

it’s already available.

Editorial team

Proposals need to be valid, in order to be presented to the community at

large; that validation comes from an editorial team. The editors of the

proposals are not there to evaluate its contents: they are there to ensure

that the proposal is going through the expected steps, and that discussions

related to it remain relevant and constrained within the accepted period and

scope. They are there to steer the discussion, and avoid architecture

astronauts parachuting into the issue tracker or Discourse to give their

unwarranted opinion.

Once the proposal is open, the editorial team is responsible for its

inclusion in the public website, and for keeping track of its state.

Steering group

The steering group is the final arbiter of a proposal. They are responsible

for accepting it, or rejecting it, depending on the feedback from the

various stakeholders. The steering group does not design or direct GNOME as

a whole: they are the ones that ensure that communication between the parts

happens in a meaningful manner, and that rough consensus is achieved.

The steering group is also, by design, not the release team: it is made of

representatives from all the teams related to technical matters.

Is this enough?

Sadly, no.

Reviving a process for proposing changes in GNOME without addressing the

shortcomings of its first iteration would inevitably lead to a repeat of its results.

We have better tooling, but the problem is still that we’re demanding that

each project maintainer gets on board with a process that has no mechanism

to enforce compliance.

Once again, the problem is that we have a bunch of fiefdoms that need to be

opened up to ensure that more people can work on them.

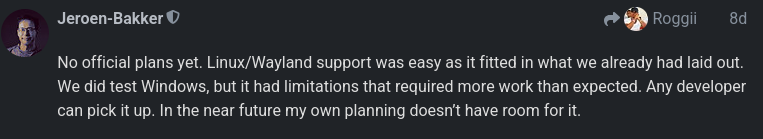

Whither maintainers

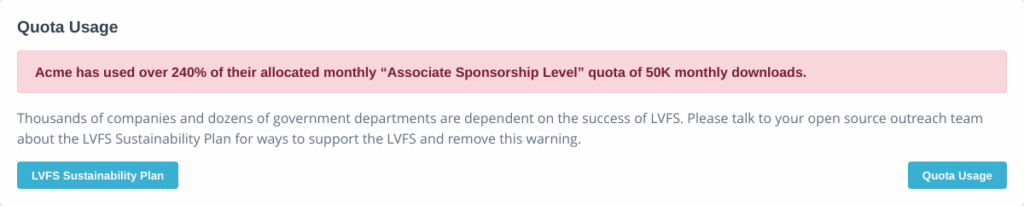

In what was, in retrospect, possibly one of my least gracious and yet most

prophetic moments on the desktop development mailing list, I once said that,

if it were possible, I would have already replaced all GNOME maintainers

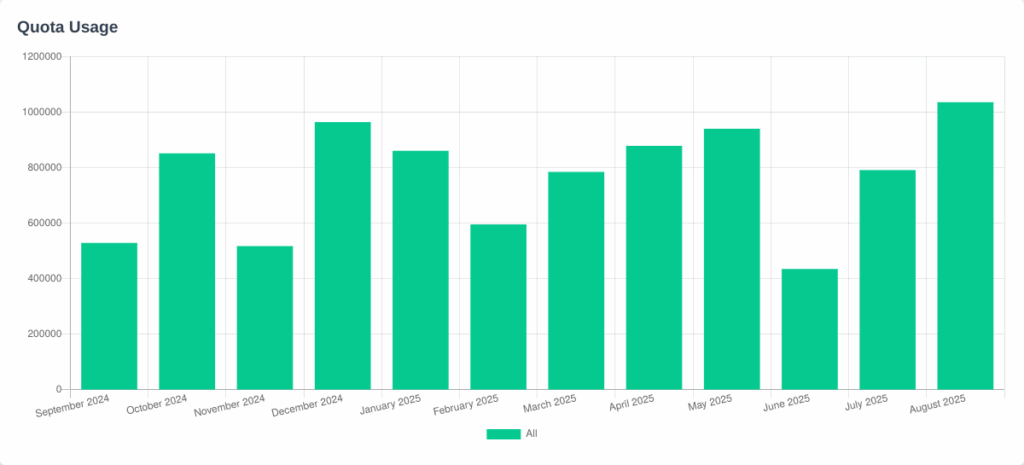

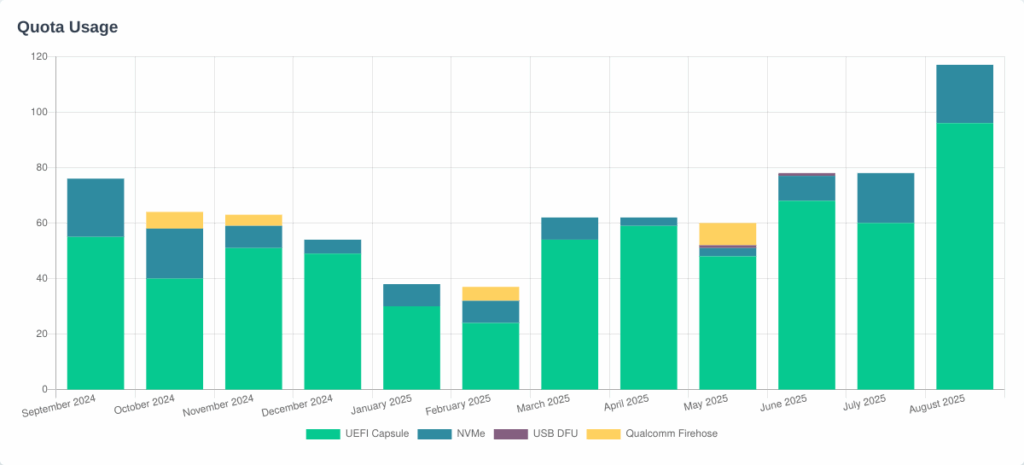

with a shell script. Turns out that we did replace a lot of what maintainers

used to do, and we used a large Python

service

to do that.

Individual maintainers should not exist in a complex project—for both the

project’s and the contributors’ sake. They are inefficiency made manifest, a

bottleneck, a point of contention in a distributed environment like GNOME.

Luckily for us, we almost made them entirely redundant already! Thanks to

the release service and CI pipelines, we don’t need a person spinning up a

release archive and uploading it into a file server. We just need somebody

to tag the source code repository, and anybody with the right permissions

could do that.

We need people to review contributions; we need people to write release

notes; we need people to triage the issue tracker; we need people to

contribute features and bug fixes. None of those tasks require the

“maintainer” role.

So, let’s get rid of maintainers once and for all. We can delegate the

actual release tagging of core projects and applications to the GNOME

release team; they are already releasing GNOME anyway, so what’s the point

in having them wait every time for somebody else to do individual releases?

All people need to do is to write down what changed in a release, and that

should be part of a change itself; we have centralised release notes, and we

can easily extract the list of bug fixes from the commit log. If you can

ensure that a commit message is correct, you can also get in the habit of

updating the NEWS file as part of a merge request.

Additional benefits of having all core releases done by a central authority

are that we get people to update the release notes every time something

changes; and that we can sign all releases with a GNOME key that downstreams

can rely on.

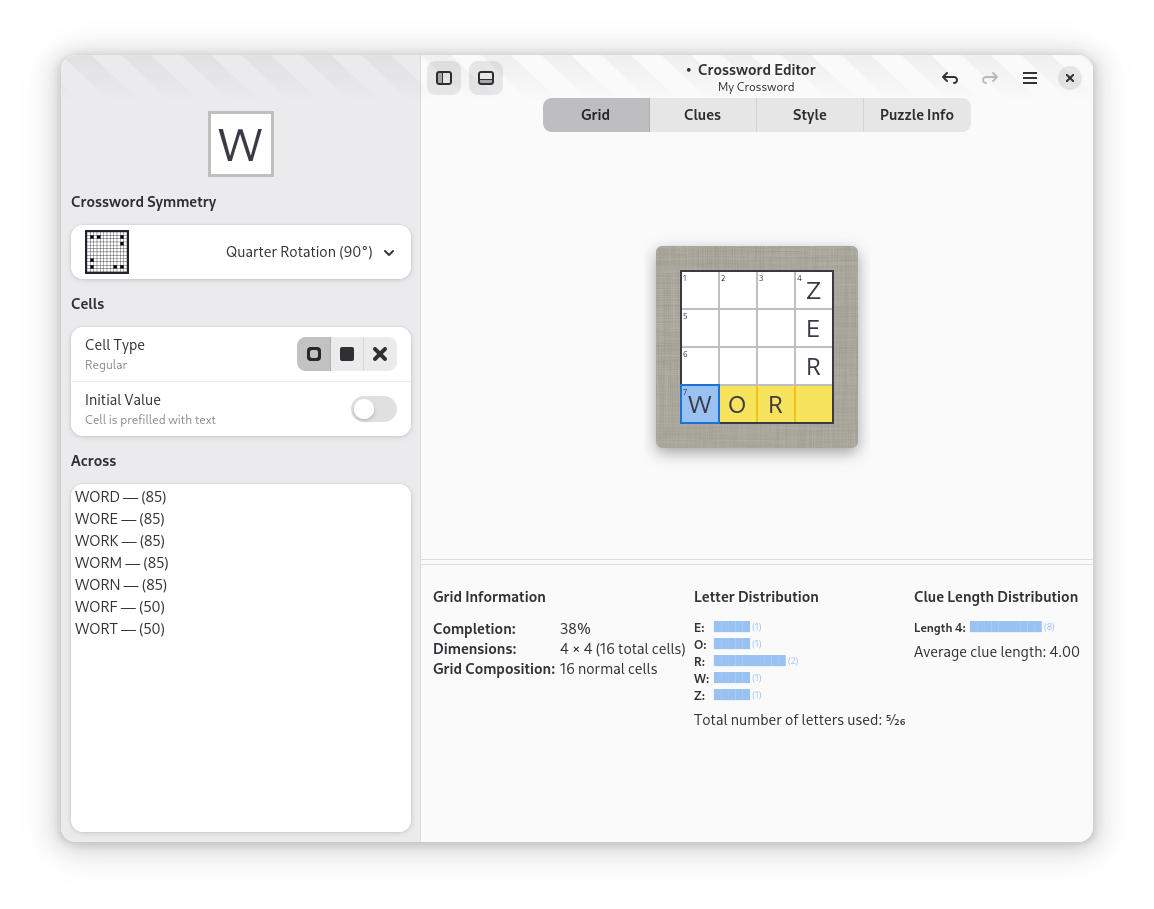

Embracing special interest groups

But it’s still not enough.

Especially when it comes to the application development platform, we have

already a bunch of components with an informal scheme of shared

responsibility. Why not make that scheme official?

Let’s create the SDK special interest group; take all the developers for

the base libraries that are part of GNOME—GLib, Pango, GTK, libadwaita—and

formalise the group of people that currently does things like development,

review, bug fixing, and documentation writing. Everyone in the group should

feel empowered to work on all the projects that belong to that group. We

already are, except we end up deferring to somebody that is usually too busy

to cover every single module.

Other special interest groups should be formed around the desktop, the core

applications, the development tools, the OS integration, the accessibility

stack, the local search engine, the system settings.

Adding more people to these groups is not going to be complicated, or

introduce instability, because the responsibility is now shared; we would

not be taking somebody that is already overworked, or even potentially new

to the community, and plopping them into the hot seat, ready for a burnout.

Each special interest group would have a representative in the steering

group, alongside teams like documentation, design, and localisation, thus

ensuring that each aspect of the project technical direction is included in

any discussion. Each special interest group could also have additional

sub-groups, like a web services group in the system settings group; or a

networking group in the OS integration group.

What happens if I say no?

I get it. You like being in charge. You want to be the one calling the

shots. You feel responsible for your project, and you don’t want other

people to tell you what to do.

If this is how you feel, then there’s nothing wrong with parting ways with

the GNOME project.

GNOME depends on a ton of projects hosted outside GNOME’s own

infrastructure, and we communicate with people maintaining those projects

every day. It’s 2025, not 1997: there’s no shortage of code hosting services

in the world, we don’t need to have them all on GNOME infrastructure.

If you want to play with the other children, if you want to be part of

GNOME, you get to play with a shared set of rules; and that means sharing

all the toys, and not hoarding them for yourself.

Civil service

What we really want GNOME to be is a group of people working together. We

already are, somewhat, but we can be better at it. We don’t want rule and

design by committee, but we do need structure, and we need that structure to

be based on expertise; to have distinct sphere of competence; to have

continuity across time; and to be based on rules. We need something

flexible, to take into account the needs of GNOME as a project, and be

capable of growing in complexity so that nobody can be singled out, brigaded

on, or burnt to a cinder on the sacrificial altar.

Our days of passing out in the middle of the dance floor are long gone. We

might not all be old—actually, I’m fairly sure we aren’t—but GNOME has long

ceased to be something we can throw together at the last minute just because

somebody assumed the mantle of a protean ruler, and managed to involve

themselves with every single project until they are the literal embodiement

of an autocratic force capable of dragging everybody else towards a goal,

until the burn out and have to leave for their own sake.

We can do better than this. We must do better.

To sum up

Stop releasing individual projects, and let the release team do it when needed.

Create teams to manage areas of interest, instead of single projects.

Create a steering group from representatives of those teams.

Every change that affects one or more teams has to be discussed and

documented in a public setting among contributors, and then published for

future reference.

None of this should be controversial because, outside of the publishing bit,

it’s how we are already doing things. This proposal aims at making it

official so that people can actually rely on it, instead of having to divine

the process out of thin air.

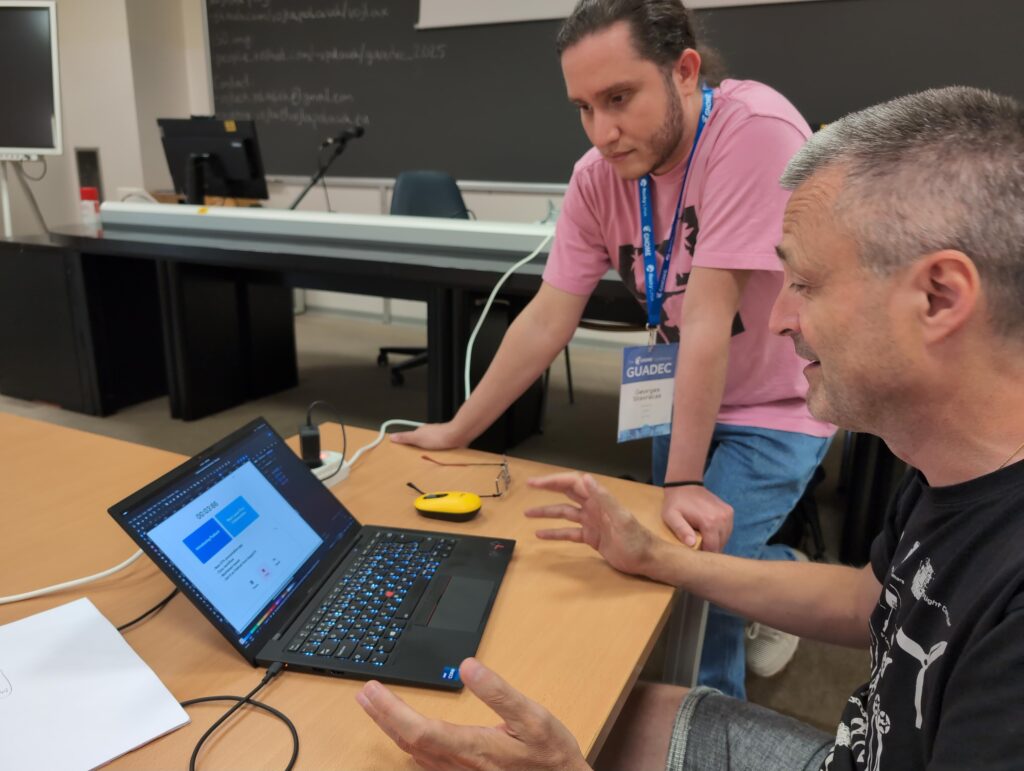

The next steps

We’re close to the GNOME 49 release, now that GUADEC 2025 has ended, so

people are busy working on tagging releases, fixing bugs, and the work on

the release notes has started. Nevertheless, we can already start planning

for an implementation of a new governance model for GNOME for the next cycle.

First of all, we need to create teams and special interest groups. We don’t

have a formal process for that, so this is also a great chance at

introducing the change proposal process as a mechanism for structuring the

community, just like the Python and Rust communities do. Teams will need

their own space for discussing issues, and share the load. The first team

I’d like to start is an “introspection and language bindings” group, for all

bindings hosted on GNOME infrastructure; it would act as a point of

reference for all decisions involving projects that consume the GNOME

software development platform through its machine-readable ABI description.

Another group I’d like to create is an editorial group for the developer and

user documentation; documentation benefits from a consistent editorial

voice, while the process of writing documentation should be open to

everybody in the community.

A very real issue that was raised during GUADEC is bootstrapping the

steering committee; who gets to be on it, what is the committee’s remit, how

it works. There are options, but if we want the steering committee to be a

representation of the technical expertise of the GNOME community, it also

has to be established by the very same community; in this sense, the board

of directors, as representatives of the community, could work on

defining the powers and compositions of this committee.

There are many more issues we are going to face, but I think we can start

from these and evaluate our own version of a technical governance model that

works for GNOME, and that can grow with the project. In the next couple of

weeks I’ll start publishing drafts for team governance and the

power/composition/procedure of the steering committee, mainly for iteration

and comments.

)

)

Until next update!

Until next update!